Fader: What It’s Really Like Inside N.Y.C.’s Vibrant Young Vogue Scene

The Sara Jordenö-directed documentary Kiki provides an intimate look into the contemporary black and Latinx gay ballroom scene.

Sitting on the Christopher Street Pier a few summers ago, I saw a young black queer kid wearing headphones and dancing. It was the middle of the day, and he jumped into the air and landed on his back, one leg beneath him, in a death drop. “Yasssssss,” a black gay man encouragingly shouted. “She can vogue,” he said to no one in particular. The dancer then broke into duck walking before falling onto the grass. “I’m practicing for a Kiki ball,” the youth later told the older black queen.

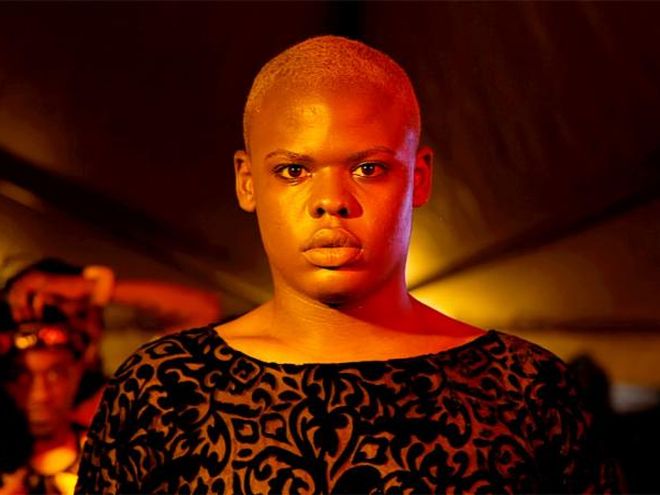

Kiki, a new feature-length documentary directed by Sara Jordenö and co-written by Twiggy Pucci Garçon, introduces audience-goers to this vibrant community and culture in its modern-day form. The film takes place three decades after the release of Paris Is Burning, the 1990 documentary that chronicled N.Y.C.’s black and Latinx gay ballroom scene during the 1980s. (Garçon’s co-writing credit seems to allow for the subjects to control the way their narratives unfold on screen. A long overdue nod to the subjects of Paris Is Burning, who felt its director Jennie Livingston had taken advantage of them.) Unlike Paris Is Burning, which is rife with scenes of founding house mothers and fathers, Kiki follows the lives of its progeny — Garçon, his best friend Chi Chi Mizrahi, Divo Pink Lady, and two young black trans women, Gia Marie Love and Izana “Zaryia Mizrahi” Vidal — all legendary and all up-and-coming. Like the generations before them, they are figuring out a way to collectively survive their “transitions,” as Gia Love puts it in one of the film’s opening shots. It doesn’t take long to realize: these ballroom-scene youth want to turn their perseverance into an emblem of triumph; they want their stories to be a victory of the QTPOC imagination over AIDS and an America that has done its very best to shut them out.

By stylizing survival, N.Y.C.’s black and Latinx queer community in the late ‘70s and ‘80s were forced to create safe spaces on the Christopher Street Pier and in clubs around Manhattan — ports of peace and belonging that were given the title “Paris.” These spaces established a culture of QTPOC fantasy, dreamed up by a hamstrung generation who lived entirely on the borders of society. Pepper LaBeija, Dorian Corey, Angie Xtravaganza, and Willi Ninja, all icons of Paris, held drag balls inspired by the ones hosted in Harlem at Rockland Palace in the ‘20s. There, they fashioned new identities, invented vogue, created new music — the ballroom scene’s DJ Mikeq and his music collective Qween Beats soundtracks Kiki with vogue beats — and lived out denied desires that ended in death for many of them and their friends.

The kiki scene, a youthful offshoot of the traditional ballroom scene, unearthed for the mainstream in Paris Is Burning, has fully emerged in the past decade. Kiki depicts a dynamic community that uses vogue and ball competitions to foster youth development for queer kids of color. In one scene, shot at the Seward Park Extension, the House of Pink Lady convenes. Divo Pink Lady, who grows more comfortable expressing his sexuality as the film progresses, spins into the air and vogues across the floor. The house chants and claps, while in another section of the rec room Omari Mizrahi holds a group circle, providing a lesson on realness. “In ballroom we can be whatever we want to be,” he says. “You know what I’m saying? I can choose to be masculine or feminine. In this house, I don’t want us to have labels, simply this: you walk realness, doesn’t matter what realness it is, but you know because it’s you.” Omari then holds a class where the kids model the self confidence he instills in them. “Yeah,” he says, eyeing a butch queen, “I am looking for you to sell it.”

But the film’s moments of true empowerment are hindered by realities filled with abandonment, sexual exploitation, health problems, and discrimination: Garçon loses his apartment in one true-to-life scene, temporarily becoming homeless after his landlord evicts him without warning; after deciding to transition upon joining the kiki community, Zaryia Mizrahi’s own family disowns her; there’s also the moment at which the community fully comes together to eulogize Travis, one of their own who passed away from HIV-related afflictions. “Our community is on very intimate terms with death; that comes from complications with HIV, it comes from police brutality, it comes from all sorts of health issues, it comes from suicide, it comes from hate crimes, it comes from a lot of things,” Garçon said during the candlelight vigil honoring Travis’s life. Later, standing on an uptown street corner, Divo Pink Lady considers all that he’s gone through: “I don’t like to let my situation run my life, because there’s always something out there worse than yours.”

That may be true, but his reality — as well as the reality of those in the scene — is a harsh reminder that new cultures are often born of people who have been ostracized from outdated iterations. These are people demanding to be seen for all of who they are, no matter the cost. And so: again and again the film’s characters gather to kiki, forced to build a space of their own in a society that still refuses to make room for the black and brown queer existence.

In one of the film’s more charged exchanges, Gia Love walks down the street as a young black boy yells, “Fagggooot.” Resilient as ever, she responds, “Your mother’s a faggot!” From behind the camera, the director inquires about her state — Is she okay? What is she feeling in the moment? “No, I’m triggered,” Love explains, looking utterly powerless for the first time in the entire film. The street scene cuts to Love asking herself, “Who was I before ballroom?” An image of Love before her transition flashes across the screen. “I was a person who was lost,” Love says. “I was a person who wasn’t confident in my ability to do and because I found a community that appreciates me — all of me — I’m able to be myself.” (Sitting on their living room couch surrounded by Love’s siblings, Love’s biological mother offers one of the most memorable expressions of black love in the film: “She called me three years ago and said, ‘Ma, I made a decision to live my life as a woman,’” her mother recalls. “I said, ‘What?’ Then I thought about it while she was on the phone and I said, ‘Whatever your decision is I’m with you.’ I accept it.” She pauses, “I think she’s sexy. Like me, feel me?”)

The unevenness of their intersectional experiences come to light near the end, when the Supreme Court ruling on marriage equality is announced. Without a flicker of emotion, Garçon reads President Obama’s statement on the court’s decision. “We still have to fight for our equality in the workplace, we still have to fight for LGBTQ homeless, we still have to fight for trans rights. There’s so much left,” Garçon says. And it’s here, even amid celebration, where the heaviness of the realities that they must still endure on a daily basis bears down on them with great force.

Kiki is a film about progress, but there are no clear victories in the stories told. Every gain is a result of a traumatic circumstance tied squarely to the subject’s race and sexuality. And yet, in the kiki scene, where these young voguers can do more than just survive, they have found another Paris, burning red hot.

This article was originally published on Fader.com and written by Antwaun Sargent